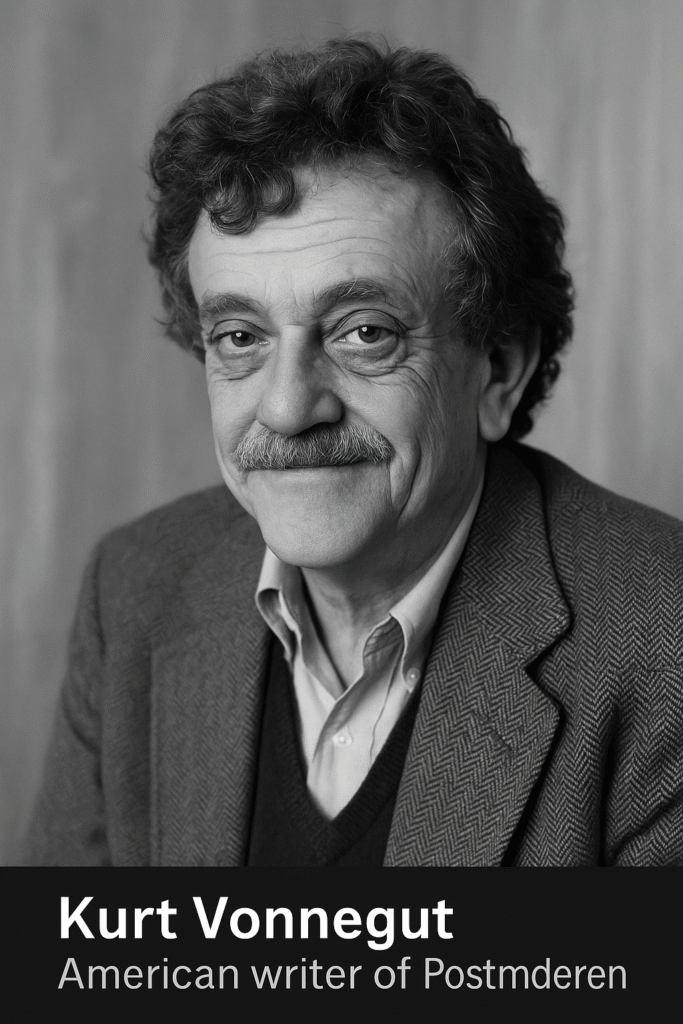

Early Life and Formative Influence

Kurt Vonnegut was born on November 11, 1922, in Indianapolis, Indiana. His childhood unfolded in a troubled America. The Great Depression destroyed his family’s finances. His father, once a proud architect, lost clients and hope. His mother, disillusioned, struggled with mental health. These personal losses left deep scars.

Even as a boy, Vonnegut noticed contradictions. He saw cheerful advertisements in a broken economy. He heard patriotic slogans while witnessing suffering. These early paradoxes became foundations for his fiction. They taught him irony, contradiction, and the false promise of progress.

He studied biochemistry at Cornell. Still, his passion remained writing and satire. He edited the college paper. There, he honed his style—brief, biting, and bold. Later, World War II intervened. His role as a soldier would define him forever.

War, Trauma, and Moral Awakening

Vonnegut joined the U.S. Army and was shipped to Europe. During the Battle of the Bulge, Germans captured him. He became a prisoner of war in Dresden. He worked in an underground meat locker. Above ground, the city turned to fire.

The Allied bombing of Dresden killed over 130,000 people. Kurt Vonnegut survived by pure chance. What he saw—piled bodies, melting glass, burnt silence—never left his memory. That horror became the center of his most famous novel.

This event didn’t just shape him emotionally. It shaped his philosophy. He rejected glory. He hated violence. He questioned meaning. War didn’t make heroes. It made orphans and widows. It created madness, not pride. Vonnegut returned to America forever changed.

Literary Debut and Narrative Breakthrough

Kurt Vonnegut American writer began his career in the 1950s. He worked as a journalist and PR man. His first novel, Player Piano, appeared in 1952. It explored automation, alienation, and dystopia. Though modest in success, it revealed his future direction.

Soon, Vonnegut found his true rhythm. His voice merged satire with sorrow. His imagination blended science fiction with absurdity. He didn’t write escapist fantasy. He wrote about a world too real and too strange.

His 1963 novel Cat’s Cradle brought critical praise. The book mocked scientific arrogance and religious lies. Through the fictional religion Bokononism, he exposed human self-deception. The phrase “busy, busy, busy” became a metaphor for life’s pointless chaos.

Vonnegut’s writing grew sharper. He began breaking rules. He interrupted plots. He addressed readers directly. He even inserted himself into stories. These techniques made him a postmodern pioneer.

Slaughterhouse-Five: War, Time, and Madness

In 1969, Vonnegut published Slaughterhouse-Five. This novel became his masterpiece. It combined autobiography, science fiction, and anti-war satire. The protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, becomes “unstuck in time.” He jumps across moments—war, peace, childhood, alien abduction.

Each time someone dies, Vonnegut writes, “So it goes.” These three words repeat like a ritual. They show numb acceptance. They highlight life’s unstoppable violence. Readers become aware of death, but not overwhelmed.

Vonnegut also appears in the book himself. He tells us the story’s limits. He admits its failings. This metafictional device dismantles illusion. It reveals the author’s doubt, fatigue, and need to bear witness.

The novel doesn’t glorify war. It doesn’t explain suffering. Instead, it accepts life’s fragmentation. Through nonlinear scenes and absurd characters, Vonnegut mirrors human confusion. His narrative becomes both satire and sorrow.

Defining Features of His Postmodern Style

Kurt Vonnegut American writer embraced postmodernism with unique clarity. His fiction rejected realism. He favored irony, parody, and play. His sentences were short, his meanings layered.

He used unreliable narrators. He often broke the fourth wall. He interrupted his own stories. He drew crude illustrations. These acts disrupted traditional expectations. They forced readers to reflect, not escape.

He also undermined authority. Institutions—military, political, religious—became targets of mockery. Leaders looked foolish. Scientists seemed reckless. Prophets told comforting lies. Nothing sacred remained untouched.

Vonnegut’s humor was sharp. Yet it was never cruel. He laughed to survive pain. He joked to expose horror. His satire gave readers truth hidden in absurdity.

Key Works and Their Themes

Vonnegut’s bibliography reveals his evolution. Each book deepened his critique. Each story blended genres. He used fiction to tackle real fears.

Cat’s Cradle (1963)

Here, he questions science and religion. Ice-nine, a fictional chemical, ends the world. Bokononism, a fake religion, comforts survivors. Truth becomes irrelevant. Belief becomes survival.

God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1965)

This novel attacks capitalism and inherited wealth. Eliot Rosewater tries to help the poor. Society labels him insane. The book asks: Can compassion survive greed?

Breakfast of Champions (1973)

Vonnegut deconstructs storytelling itself. He draws cartoons. He appears in the plot. He even frees characters from fiction. The book becomes an act of rebellion.

Mother Night (1961)

A spy pretends to be a Nazi. His performance becomes identity. Vonnegut warns: “We are what we pretend to be.” Truth and role blur.

Galápagos (1985)

In the future, humans evolve into simple animals. Brains shrink. Society vanishes. Intelligence becomes a curse. Evolution mocks civilization.

Each book repeats core themes—war, absurdity, free will, and survival. Yet each takes a new form. He never wrote the same story twice. He always experimented.

Humor as Weapon and Shield

Kurt Vonnegut used humor with purpose. He didn’t entertain. He exposed. His laughter hurt. Yet it healed.

He faced horrors—bombings, death, lies. But he chose jokes. Not to dismiss pain. But to endure it. Humor helped him breathe. It helped readers see truth.

His humor wasn’t cheap. It wasn’t light. It carried anger, grief, and wisdom. He turned tragedy into irony. He turned despair into parody.

He once said, “If I die—God forbid—I hope you will say: ‘Kurt is up in heaven now.’ That’s my favorite joke.” That joke, dark and sweet, captures his soul.

Language, Form, and Precision

Vonnegut’s prose was stripped and sharp. No long words. No excess. Just clarity. His writing spoke plainly. Yet it held deep meaning.

He mastered brevity. One sentence did the work of five. He avoided fluff. He respected time. Readers never got lost. But they always found ideas.

He also bent form. He used sketches. He used repetition. He used space as punctuation. Every choice had a purpose. Every page reflected his vision.

His form served function. His simplicity served depth. He didn’t impress. He connected.

Last Works and Public Presence

In later years, Vonnegut became a public thinker. He gave speeches. He published essays. He criticized war, greed, and media. He spoke for the disillusioned.

A Man Without a Country (2005) collected his essays. It showed him still fierce. Still funny. Still angry.

He warned against war. He mocked politicians. He mourned lost values. But he never lost hope entirely. He still believed in kindness.

Vonnegut passed away in 2007. He left behind words, ideas, and laughter. He left a path for others.

Enduring Legacy and Cultural Impact

Kurt Vonnegut American writer influenced generations. Writers cite him. Teachers teach him. Readers quote him.

He shaped postmodern fiction. He made satire meaningful. He made pain readable. He made readers laugh and cry.

His books remain in print. His ideas circulate widely. He appears in memes, protests, and classrooms. His voice still matters.

He changed what novels could be. He made literature playful, powerful, and personal. He gave fiction a human face.

Final Thoughts

Kurt Vonnegut American writer showed truth in absurdity. He mixed aliens with war, cartoons with tragedy. His fiction taught survival. His laughter healed wounds.

He didn’t offer answers. He offered honesty. He didn’t pretend. He revealed. Through short chapters and simple words, he changed minds.

Even today, in chaotic times, Vonnegut speaks clearly. His humor cuts through lies. His sadness meets ours. He reminds us to care, to notice, and to endure. So it goes.

Samuel Butler, Restoration Period Writer: https://englishlitnotes.com/2025/07/03/samuel-butler-restoration-period-writer/

Thomas Pynchon Postmodern Writer: https://americanlit.englishlitnotes.com/thomas-pynchon-postmodern-writer/

The Thirsty Crow: https://englishwithnaeemullahbutt.com/2025/05/10/the-thirsty-crow/

Subject-verb Agreement-Grammar Puzzle Solved-45:

https://grammarpuzzlesolved.englishlitnotes.com/subject-verb-agreement-complete-rule/

Discover more from Welcome to My Site of American Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.